Can an orchestral harp part illustrate both effective and ineffective writing?

The harp part to Paul Dukas’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is a prime example. This wildly exciting piece requires substantial rewrites for the harp, but also effectively uses the harp in the orchestral timbre. We will work through this piece down together and walk away with both effective orchestration ideas, as well as how to avoid specific pitfalls.

My name is Danielle Kuntz, new music harpist and harp notation coach, and I am here to help you learn how to write for the harp with creativity and confidence.

Prefer to learn on video? Watch here:

Why The Sorcerer’s Apprentice?

Many of you ask me for suggestions of good harp parts to study to learn how to write for the harp. This question is difficult to answer because most harp parts are not 100% good or 100% problematic. Most standard harp parts, like The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, include both effective and ineffective elements within the same piece. Rather than simply giving a list of scores to study, my goal is to create comprehensive reviews to provide the context for these well-known harp parts. (You can find these reviews on the Harp Tips Blog and corresponding YouTube channel.)

Key spots for the harp in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

In this review, we will discuss the factors of Orchestration, Technique Challenges, and Common Rewrites within the following sections:

Beginning – Rehearsal 2: Harmonics

Rehearsals 15-16: Enharmonics for repeated notes

Rehearsals 19-20: Jumps

Rehearsal 22: Double vs. Single Glissandi

Rehearsal 26-27: Tempo

Rehearsals 28-30: Tempo and Jumps

Rehearsal 36-41: Enharmonics for repeated notes

Rehearsal 49-51: Too dense

Rehearsal 52: Interval Spans

If you want to follow along with the score or harp part, you can access it on IMSLP here.

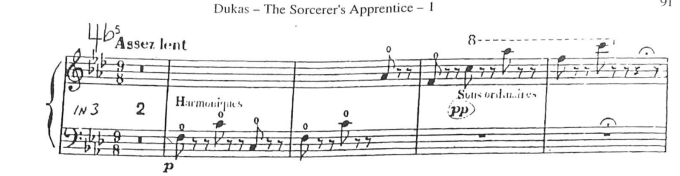

Beginning – Rehearsal 2: Harmonics

The opening of this piece uses harp harmonics to accompany the clarinet melody. The timbre of these two instruments blend together beautifully, especially with the thin overall orchestral texture. (The harp enters at 0.18.)

When you look at the harp score, you will notice that the last four notes in each phrase are not harmonics.

Due to the shorter string length, last four high notes fall outside of the reliable range for harmonics. While they might be possible on some harps by some harpists, the sound would still be too thin to project in an orchestral context. In this piece, the transition between harmonics and non-harmonics is fairly seamless since the timbre of the harp’s high register sounds quite similar to mid-register harmonics.

(Learn more about harmonic ranges and notation here.)

Rehearsals 15-16: Enharmonics

The harp is one of the few instruments that can play true enharmonics. Enharmonic is defined as: Relating to notes that are the same in pitch (in modern tuning) though bearing different names (e.g., F sharp and G flat or B and C flat). (Oxford Languages)

On the harp, enharmonic notes are two notes that are the same pitch, but played on different strings (with different pedal configurations.)

(Learn more about ENHARMONICS here.)

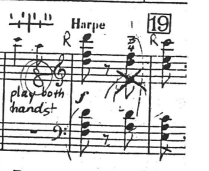

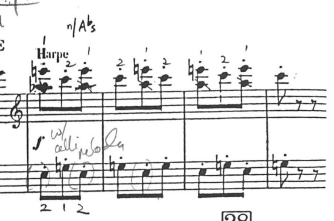

In this section, harpists will standardly play the last Eb as a D# to avoid a quickly repeated string between the right hand and left hand. (The shorthand notation for an enharmonic is a circled note.)

Side note: Due to the speed, both hands play the enharmonic D# to retain parallelism, even though the enharmonic is only necessary in the left hand.

Do I need to write enharmonic notes in the score?

Not necessarily. Enharmonics can be subjective and do not always simplify the part. However, in faster sections, you can be aware of available enharmonics in order to provide options to the harpist. (You can also consult with a harpist to get a second option on enharmonics within the context of your piece.)

Hypothetically, if this passage required a D-natural or D-sharp on the harp, this solution would not be available.

SPOILER: Later in this piece, we will see what happens when enharmonics are not available.

Rehearsals 19-21: Jumps

This is the first section that requires leaving out notes. If you compare the right hand with the left hand, you will notice that the the left hand stays mostly within the same seven-note range. However, the right hand has a large jump down from beat 1 to beat 3 and back up to the next beat 1. At this tempo, the jump jeopardizes both accuracy and volume – this is a case where fewer notes may actually result in more volume.

Reminder: Fewer notes may result in greater volume

One rewrite option is to drop the left hand and have the left hand take beat 3 in the top line. The solution I like is to drop the low F# on beat 3 in the right hand. This solution eliminates the jump in the right hand and allows it to stay in the same range.

In fast passages, be mindful of each hand’s range and jumps.

Another note for this section is the use of enharmonics at rehearsal 21. Since we already have an E-natural pedal from rehearsal 20, it makes more sense to substitute E-natural for F-flat since it reduces pedal changes. It also provides a slightly better hand shape for the right hand since larger intervals between the top two fingers (thumb and index) is more natural. (See How to Voice Chords and Arpeggios Like a Pro.)

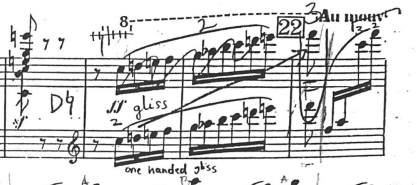

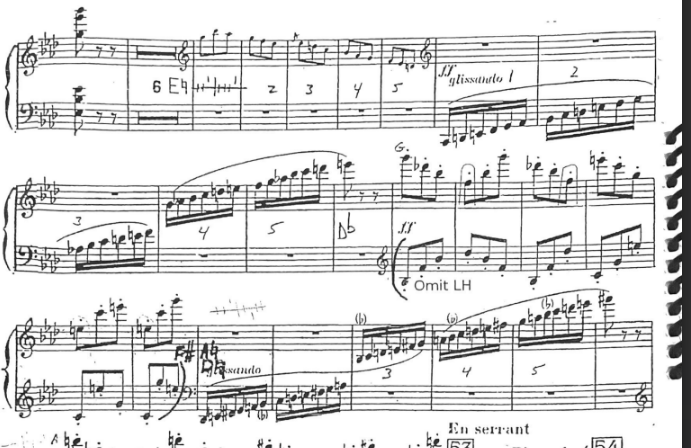

Rehearsal 22: Double vs. Single Glissandi

“When should I use double vs. single glissandi? Will double always be louder?”

The answer to this question depends on the context, or specifically, where the glissando is starting from and what happens after the glissando. In this particular section, the harp part is quite dense and requires quick jumps, both two and from the glissando.

In this case, a single glissando minimizes the jumps and will result in a louder glissando AND more security in the following section.

If a glissando has something immediately preceding or following it, a single glissando will be played louder.

Rehearsal 26-27: Finger Independence

A small rewrite on the top line is required in this section due to the tempo and necessary finger independence. On the piano, this section would work, since a pianist could pair strong fingers to quickly oscillate between 1/5 and 3.

However, on the harp, the motions of playing take more time. The sideways hand position results in less finger facility and speed than the piano position. (Try to air play in the two positions and you will see the difference.) Ultimately, this cross pattern is not practical to place and replace at the given tempo.

The best solution is to drop the A-flat in the right hand. While this does leave out a harmony note, the overall orchestral texture is too loud for the harp to provide structural harmony. (I.e. this pitch is doubled elsewhere.)

The role of the harp in sections like this is to add color, not provide critical harmonies. This principle continues to apply in the next few sections.

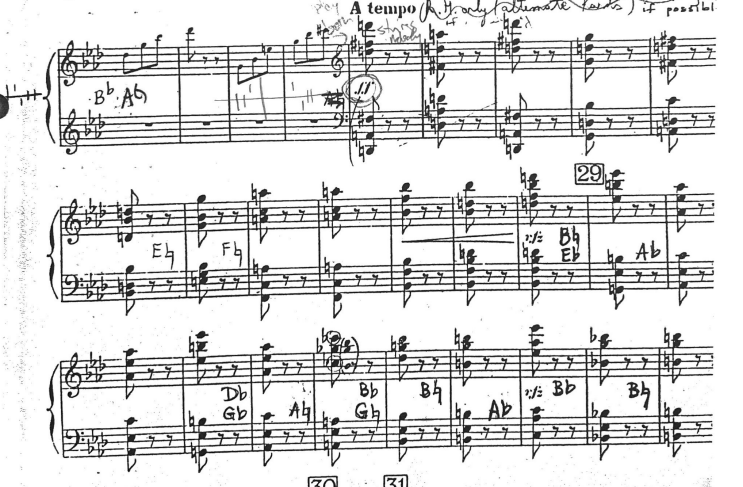

Rehearsals 28-30: Tempo and Jumps

This section has three difficult factors: tempo, left hand jumps, and pedal changes.

If this piece is played at the traditional tempo, the left hand is nearly impossible, especially when paired with the pedal changes. Out of these three variables, the left hand makes the most sense to drop for the following two reasons:

The mid-low register of the harp does not project well in loud orchestration.

Even if all the notes were played, the left hand would likely not be heard, since it is playing in the mid-low register of the harp. In large ensemble, the timbre of the high register tends to project and add more to the overall texture.

Higher risk of buzzing with the left hand jumps

Similarly, because of the slower vibrations of the lower strings AND the jumps, the left hand line is at higher risk for buzzing.

Additionally, with removing the complication of the lower chords, the top voice will likely be played louder and add more to the overall color.

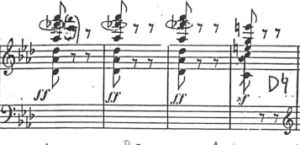

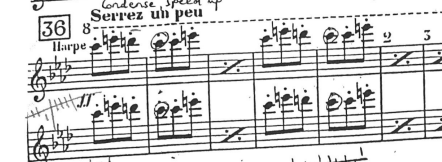

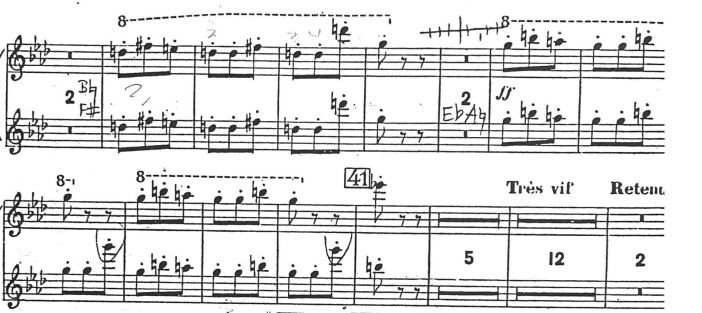

Rehearsal 36-41: Enharmonics for repeated notes

In general, repeated notes are not effective on the harp, especially at such a quick tempo. There simply is not enough time to replace the string and play again at ff. So, throughout this section, harpists traditionally use enharmonic notes to avoid the repeated notes.

This strategy works as this sequence moves up by step. However, at 12 after Rehearsal 40, enharmonic notes are no longer possible. Due to the pedal configuration only allowing flat-natural-sharp, the harp does not have an enharmonic equivalent for D-natural and G-natural. This is a section where we “do the best we can”, but general have to leave out the second repeated note. Will the lack be heard in the orchestration? Probably not.

When using enharmonic notes as a workaround for repeated notes, ensure that an enharmonic equivalent is available.

Rehearsal 49: Too dense

This section is simply too dense to play as written at the given tempo. Remember that the orchestral dynamic is ff, which means that the harp is simply there for color and not to add audible sound.

Fewer notes played louder have a greater chance at being heard.

The common rewrite is to leave out beat 1 in the right hand and beat 2+3 in the leave hand. This solution relies on uses the strongest, most powerful fingers on each hand.

Uses the power of the left hand thumb for the downbeat instead of the right hand 4th (or ring) finger.

Uses the power of the right hand thumb for the downward arpeggio, rather than the left hand 4th (or ring) finger.

This rewrite gives a little extra punch and increases the chance of being heard, even if just a little.

Rehearsal 52: Interval Spans

The final rewritten section is problematic for two reasons:

First, the tempo is too fast for non-parallel arpeggios in both hands.

Second, the left hand interval spans would be nearly impossible at any tempo, especially the last two measures of the phrase. Any interval larger than a 10th requires placing notes individually, which is only feasible at much slower tempi. Additionally, how much time is provided to jump between the left hand arpeggios and the glissando? Just a thought.

The best solution here is to drop the left hand and divide the right hand part between the two hands.

Summary

Even though we have highlighted numerous impossible sections, this piece is still a great example of the use of the harp’s timbre in the orchestration. We see this both in the solo harmonic sections, but also in how the harp provides coloristic support in the louder sections.

Remember that “less is often more” and to strategically use the harp’s registers to support the orchestration.

Keep it simple.

Join the Discussion

Have you used any of these strategies in your own orchestration? Are there other pieces you would like to see reviewed here? Let me know in the comments!

Stay Connected

Sign up for the Harp Tips Emails for more harp composing and harp writing strategies and resources.