Enharmonics.

You may be wondering why harpists always talk about this concept.

For most instruments, ‘enharmonics’ are redundant. Yes, E# the same as F. On the piano, it is exactly the same key!

However, on the harp, enharmonics provide a way to work around some of the inherent limitations.

In this post, we will discuss practical uses for enharmonics, including repeated notes and pedal solutions.

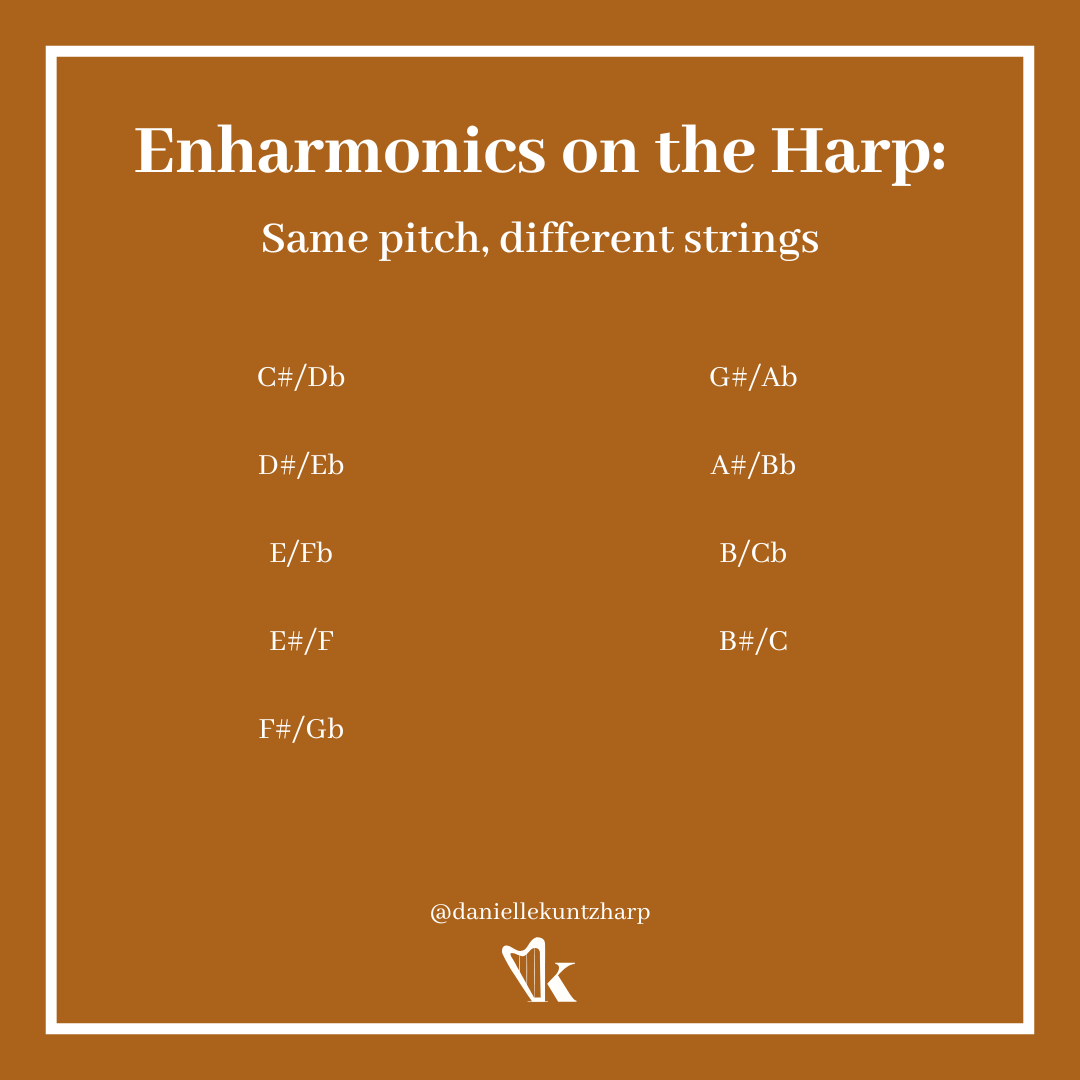

But first, what is an enharmonic? Enharmonic is defined as: Relating to notes that are the same in pitch (in modern tuning) though bearing different names (e.g., F sharp and G flat or B and C flat). (Oxford Languages)

On the harp, enharmonic notes are played on different strings. A C is always played on the C string, whether it is flat, natural, or sharp. A D is always played on the D string, whether it is flat, natural, or sharp. Hence, even though a C# and Db are “enharmonic”, they are still played on separate strings. This means that the pedal positions will be different, the finger patterns may be different, etc.

However, remember that because the harp is diatonic (the unchanged strings spell a major scale), not every note has an enharmonic equivalent.

Enharmonics as repeated notes: On the harp, repeated notes (i.e. the same string) are only possible at a slower tempo. Since each string must be placed in advance before playing, rapid repeated notes are impractical at best. (See posts under #fourmotionsofplaying)

However, if the repeated pitches use two different strings, it can be incredibly idiomatic, even at a trill speed.

(Note: the two strings will have a slightly different timbral sound and the effect is very similar to a timbral trill on wind instruments)

Parish-Alvars La Mandoline, Op. 84 is an excellent example of this technique.

In this example, the enharmonics are implied rather than written out (repeated Cs instead of B#-C-B#-C, etc. In general, in modern harp notation, it is preferred to write out the played spellings vs. the older notation practice seen in this score.

Finally, be aware that enharmonics for repeated notes always require extra pedal changes. Be sure to weigh the added pedal changes against the benefits of enharmonics. Sometimes, the simplest solution works best.

Enharmonics for pedal solutions: Enharmonics can also be used for alternate pedal or lever solutions.

A quick review: pedal change practicality depends on whether the pedal is on the right or left side of the harp. Each foot can only change one pedal at a time (at least 99% of the time), so two simultaneous pedals on the same side of the harp are impractical at best.

With enharmonics, you can often move a pedal change to a different foot. For instance, you can swap D# for an Eb, or A# for Bb.

(Pedal layout: (L) D C B | E F G A (R))

At a larger level, you can use enharmonics to minimize quick shifts between sharp key areas and flat key areas. Even if you end up playing in a theoretical key (like Fb major), that can end up requiring fewer pedal changes when shifting from Eb major to Fb major to F major.

The standard rewrite from Carlos Salzedo for Wagner’s Magic Fire Music is an excellent example this:

Bottom line: Enharmonic possibilities provide excellent idiomatic workarounds for techniques that are otherwise highly unidiomatic.

If you want to learn more about writing for the harp, be sure to subscribe to my email list for weekly Harp Tips emails!